Decolonizing Water

“Mni Wiconi” or “Water is Life” is a belief held by Indigenous people that gained mainstream media recognition in 2016 during the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline. In 2016, the Indigenous people living on the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota led one of the largest nonviolent resistance movements against the 1,172 mile-long pipeline. This resistance movement united hundreds of Indigenous tribes across the world with environmental activists and scientific researchers. They all lived on a camp in the Standing Rock reservation, known as Sacred Stone Camp. The movement against DAPL highlighted the lack of representation Native Americans have in the mainstream media and how often this population is excluded from the national dialogue. After seeing a stark difference in how the "water protectors" were being portrayed in mainstream media coverage versus the citizen journalism being streamed online, I wanted to photograph the daily, intimate moments both within the camp and on the front lines. The Dakota Access Pipeline movement is a painful reminder of the United States history of colonialism and its perpetuation in present-day times.

Alex Good Cane Milk, a Sioux Native American from Yankton, SD, talks about his role as an International Indigenous Youth Council organizer. "We started this movement to give the youth a voice and to promote awareness and unity. We bring people together and get stuff done," says Alex. The Youth Council plans to return to traditional values in order to survive winter at the camp. They will learn how to make tipis from elders, what vegetables are in season during the winter, and how to harvest them for survival. Alex believes that this is the best way to break free from government colonization and unite generations of Natives.

Jerica Meditz brings her new horse, Shota, to a stream so he can drink water at the Sacred Stone Camp in North Dakota. Jerica received the horse from the Standing Rock Horse Society once Shota was injured after being kicked by another horse.

Over 300 tribal flags are posted around the Sacred Stone Camp in Cannon Ball, North Dakota. The flags represent each Indian nation that have visited the camp since its founding.

Standing Rock Sioux Charles Wise Spirit and his wife, Lindsay, build a fire outside of their tent the Sacred Stone Camp. Lindsay is 9 months pregnant and expecting their third child, a boy, at any given moment.

A crane is used to dig up ground at an undisclosed location in North Dakota. The Dakota Access Pipeline spans 1,172 miles across four different states and transports an estimated 470,000 gallons of crude oil per day.

Georgia Andre smiles at her four horses before getting into her car parked outside of her home in Bullhead, SD. Andre was born in Iowa but traveled back and forth to South Dakota with her Indigenous mother frequently in her childhood. She moved back to the reservation permanently in adulthood.

Sierra Laguarde braids Salvatore Geloso's hair outside of their tipi at the Sacred Stone Camp. Salvatore, a half-Dinè musician who traveled on a school bus from New Orleans to the camp, says: "All of my friends that I traveled here with are leaving tomorrow, but I'm staying. This camp is such a spiritual place; I feel like this is where I'm supposed to be."

Nikoli Schlatter is arrested by Deputy Steve Sproul after engaging in a peaceful protest to stop a vehicle carrying Dakota Access Pipeline equipment from entering a construction site in Montrose, IA.

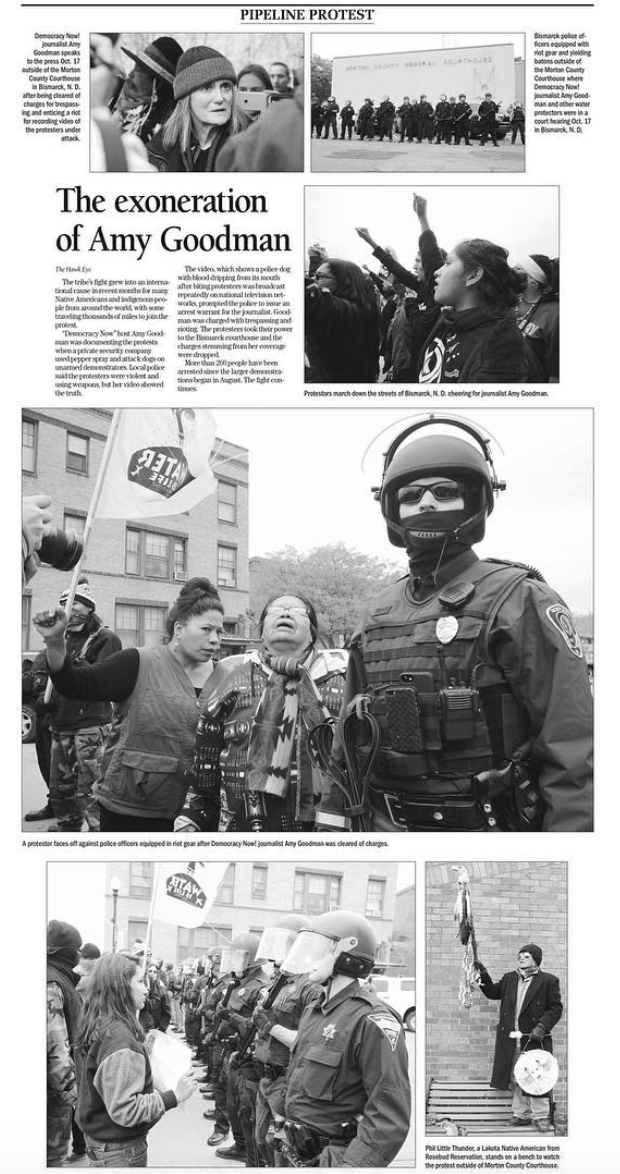

Water protectors watch police officers dressed in riot gear outside of the Morton County Courthouse, where Democracy Now! journalist Amy Goodman faces criminal charges for trespassing and enticing a riot while covering the Dakota Access Pipeline movement.

Final pieces of the Dakota Access Pipeline are fitted into the ground at an undisclosed construction location in North Dakota. The Dakota Access Pipeline spans 1,172 miles across four different states and transports an estimated 470,000 gallons of crude oil per day.

From left to right: Hunter, 12, Rayna, 10, and Frankie, 11, use spray paint to decorate a log at the Sacred Stone Camp in North Dakota. The DAPL movement focuses heavily on engaging younger generations of Indigenous people to protect the land and their rights.

Protestors march down the streets of Bismarck, North Dakota with their hands raised after Democracy Now! journalist Amy Goodman was cleared of charges for trespassing and enticing a riot.

Campers take turn chopping wood for the families living at Sacred Stone Camp to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota.

Riot gear police officers guard the front of the Morton County Courthouse during a rally for Democracy Now journalist Amy Goodman, who was charged with trespassing and enticing a riot for filming police brutality against Native American protestors.

Emerson Bobtail Bear, left, and David Red Bear Jr. hold signs at a rally for Amy Goodman, who had to make a court appearance at the Morton County Courthouse in North Dakota.

The sunset glistens on tipis at the Sacred Stone Camp in North Dakota. Over 100,000 people have visited the camp to stand in solidarity with water protectors, including over 500 Indian tribes from all over the world.

Full-story spread in the November 24, 2016 edition of The Hawk Eye newspaper, page one

Link to article: https://www.thehawkeye.com/article/20161124/news/311249952

Link to article: https://www.thehawkeye.com/article/20161124/news/311249952

Full-story spread in the November 24, 2016 edition of The Hawk Eye newspaper, page two

Link to article: https://www.thehawkeye.com/article/20161124/news/311249952

Link to article: https://www.thehawkeye.com/article/20161124/news/311249952